Migrating from Supabase

In the last couple weeks, we’ve migrated Val Town away from Supabase to a simpler database setup at Render. We’ve gotten a few questions about this, so we wanted to share what motivated the move, what we learned, and how we pulled it off. Supabase is an enormously successful product with a lot of happy users, but we ended up having a lot of problems getting to scale to our team’s needs. Your mileage may vary, but we hope our experience is a useful data point.

Background

Val Town was started by Steve Krouse in July 2022 as a site to write, run, deploy, and share snippets of server-side JavaScript. Our users describe us as “Codepen for the backend”. Folks use us to make little APIs, schedule cron jobs, and make little integrations between services, like downtime detectors, price watchers, programmatic notification services, etc.

Steve built the initial version of Val Town on Supabase. I (Tom MacWright) joined in Jan 2023.

Supabase

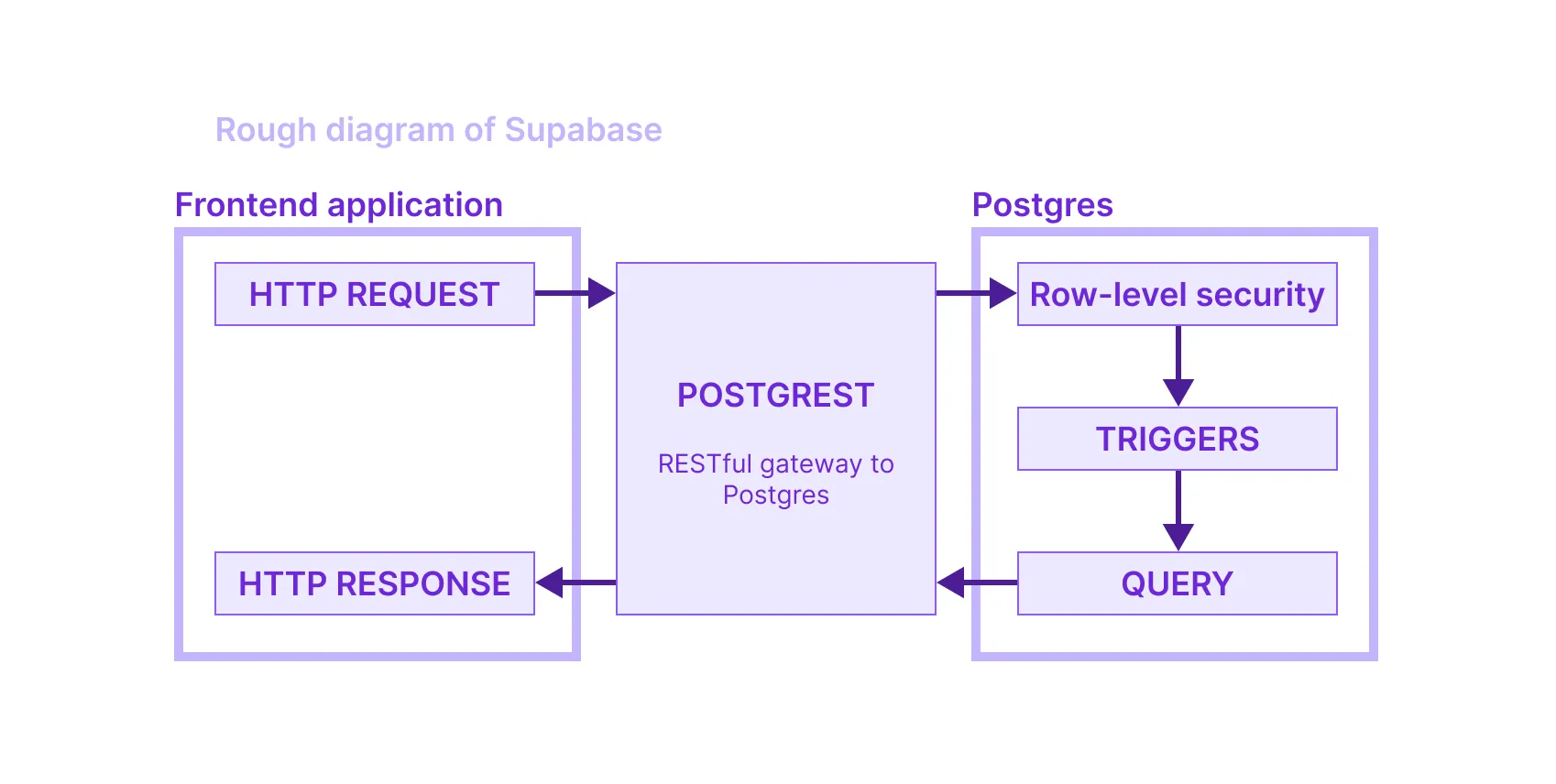

Supabase can be a way to build your entire application backend without writing a backend server. Supabase is a database, but it also gives you ways to control access with row security policies. Then it lets you query your database right from your frontend, by using PostgREST. They integrate gotrue as an authentication layer and let users sign up for your service. And finally there’s a full-fledged UI that lets you administrate the database and all of the related services without writing a line of code or using a CLI.

In effect, Supabase turns your database into an entire backend application. It does so by using every Postgres trick in the book: not just row-level security, but we were using triggers, materialized views, database roles, and multiple schemas. Postgres is a tremendously powerful platform: you can go as far as writing JavaScript embedded in SQL to write logic in the database.

When it worked well, it was spectacular: it was the speed of using Firebase, which I had heard about so many times, but with a fast-moving open source stack.

Local development was tough

The biggest problem we encountered using Supabase was local development. When I joined, all of our development happened in production: everyone connected to the production database, all of our “migrations” where performed by modifying the live database schema. We’d test migrations by duplicating tables in production and migrating them before doing it for real. Sometimes we’d use the web interface to change things like column types and indexes, which is the scariest of all – it doesn’t provide a SQL preview of what it’s about to do, and sometimes what it does is unexpected.

This, to me, was pretty scary. Usually engineering teams work with local development environments and staging environments, and only cautiously and briefly touch the production database.

Thankfully, Supabase has been developing a toolchain for local development: the Supabase CLI. The CLI manages the Supabase stack locally: Postgres, gotrue, a realtime server, the storage API, an API gateway, an image resizing proxy, a restful API for managing Postgres, the Studio web interface, an edge runtime, a logging system, and more – a total of 11 Docker containers connected together.

Unfortunately, we just couldn’t get it to work. I hit everything from broken Docker containers, to a database migration system that couldn’t handle custom roles, to missing CLI help. We weren’t able to get a local development environment working for more than a day at a time: the CLI would break, or migrations were generated incorrectly and couldn’t be applied.

Documentation

Part of the trouble with using the CLI was that the documentation isn’t quite

written yet. The command

supabase db remote commit

is documented as “Commit Remote Changes As A New Migration”. The command

supabase functions new is documented as “Create A New Function Locally.” The

documentation page is beautiful, but the words in it just aren’t finished. These

are crucial commands to document: db remote commit actually affects your local

database and tweaks migrations. It’s really important to know what it’ll do

before running it.

Unfortunately, the documentation on other parts isn’t much better: for example, the Supabase Remix integration has a decent tutorial, but is missing any conceptual or API reference documentation. Only after spending a day or two implementing the Remix integration did I realize that it would require a reset of all our user sessions because using it meant switching from localStorage to cookie-based authentication.

Downtime

Then came the downtime. Val Town is responsible for running scheduled bits of code: you can write a quick TypeScript function, click the Clock icon, and schedule it to run every hour from then on. We noticed that vals would stop working every night around midnight. After a bit of sleuthing, it ended up that Supabase was taking a database backup that took the database fully offline every night, at midnight. This is sort of understandable, but what’s less lovely is that it took a full week to get them to stop taking those backups and taking us offline.

Now, to be fair, Val town currently pummels databases. It’s a write-heavy

application that uses a lot of json columns and has a very large table in

which we store all past evaluations. And Supabase was very helpful in their

support, even helping us rearchitect some of the database schema. The

application that we’re running is, in a way, a stress test for database

configuration.

Supabase has a sort of unusual scheme for database size. Instead of pre-allocating a large database and filling it over time, databases start off small and are auto-resized as they grow. Your database starts out at 8GB, then gets upgraded once it hits 90% of that to a database 50% larger. Unfortunately, there was a fluke in this system: one Sunday, their system failed to resize our database and instead we were put in read-only mode with the disk 95% full. If you’ve dealt with systems like this before, you can guess what happens next.

If you get that close to your maximum disk size, you get a sort of catch-22: everything that you want to do to reduce the size on disk requires a little extra temporary space, space that you don’t have. Maybe you want to VACUUM a table to cut down on size - well, the VACUUM operation itself requires a little extra storage, just enough to put you over 100% of disk utilization and cause a restart. Want to try and save a few bytes by changing the type of a column? You’ll hit 100% utilization and restart.

To make matters worse, the Supabase web user interface heavily relies on the database itself - so the administration interface would crash when the database crashes. It’s nice and preferable to have separate systems: one that runs the administration interface, another that is the thing being administrated.

Anyway, after a panicked Sunday afternoon four-alarm fire, I found a table that we were no longer using, which freed up 5 gigabytes of storage and let us get out of read-only mode. A few hours later the support team responded with an update.

Database philosophy

Part of the moral of the story is that databases are hard. You could make a

company of just running databases reliably and be successful if you can be

reliable and scalable. There are whole companies like that, like

CrunchyData. Database management is a hard and

unforgiving job. But this is why we pay managed providers to be the wise experts

who know how to tune shared_buffers and take backups without interrupting

service. Sure, it’s nice to have a great user interface and extra features, but

a rock solid database needs to be the foundation.

Using Supabase as Postgres

Under the hood, Supabase is just Postgres. If you want to sign up for their service, never use the web user interface, and build your application as if Supabase was simply a Postgres database, you could. Many people do, in fact, because they’re one of the few providers with a free tier.

The hard part, though, is that if you use Supabase as a “Firebase alternative” – if you try to build a lot of your application layer into the database by using triggers, stored procedures, row-level security, and so on – you’ll hit some places where your typical Postgres tools don’t understand Supabase, and vice-versa.

For example, there are plenty of great systems for managing migrations. In the TypeScript ecosystem, Prisma and drizzle-orm were at the top of our list. But those migrations don’t support triggers, or row level security, so we would have a hard time evolving our database in a structured way while still following the Supabase strategy. So migrations would be tough. Querying is tough too – querying while maintaining row-level-security is a subject of discussion in Prisma but it isn’t clear how you’d do it in Kysely or drizzle-orm.

Using Postgres as Supabase

The same sorts of disconnects kept happening when we tried using our database as

Postgres and then administrating it sometimes with Supabase. For example, we’d

have a json column (not jsonb), but because the Studio interface was

opinionated, it

wouldn’t correctly show the column type.

Or we’d have JSON values in a table, and be unable to export them because of

broken CSV export in the

web interface. We’d see issues with composite foreign keys

being displayed incorrectly

and be afraid of issues where modifying the schema via the UI ran unexpected and

destructive queries. A lot

of these issues were fixed - the Studio now shows varchar and json types

instead of a blank select box, and should export CSVs correctly.

In both directions, it felt like there were disconnects, that neither system was really capturing 100% of its pair. There were too many things that the typical database migration query tools couldn’t understand, and also things that we could do the database directly that wouldn’t be correctly handled by the Supabase web interface.

Designing for Supabase

Unfortunately, some of the limitations of the Supabase strategy trickled into our application design. For example, we were building all of the controls around data access with Row-Level Security, which as the name implies, is row-level. There isn’t a clear way to restrict access to columns in RLS, so if you have a “users” table with a sensitive column like “email” that you don’t want everyone to have access to, you have a bunch of tough solutions.

Maybe you can

create a database view of

that table, but it’s easy to shoot yourself in the foot and accidentally make

that publicly-readable. We ended up having three user tables - Supabase’s

internal table, auth.users, which is inaccessible to the frontend, a

private_users table, which was accessible to the backend, and a users table,

which was queryable from the frontend.

We also architected a lot of denormalized database tables because we couldn’t write efficient queries using the default Supabase query client. Of course there are always tradeoffs between query-time and insert-time performance, but we were stuck at a very basic level, unable to do much query optimization and therefore pushed to either write a lot of small queries or store duplicated data in denormalized columns to make it faster to query.

I suspect that there’s a way to make this work: to write a lot of SQL and rely heavily on the database. You can do anything in Postgres. We could write tests with pgTAP and write JavaScript inside of Postgres functions with plv8. But this would buy us even more into the idea of an application in our database, which for us made things harder to debug and improve.

Where to go?

Ultimately, we switched to using a “vanilla” Postgres service at Render.

We didn’t want to self-host Supabase, because the devops issues were only part of the problem: we just wanted a database. Render has been hosting the rest of Val Town for a few months now and has been pretty great. Render Preview Environments are amazing: they spin up an entire clone of our whole stack — frontend remix server, node api server, deno evaluation server, and now postgres database — for every pull request. The Blueprint Specification system is a nice middle ground between manually configured infrastructure and the reams of YAML required to configure something like Kubernetes.

We considered a couple other Postgres hosts, like CrunchyData, neon, RDS, etc, but it’s hard to beat Render’s cohesive and comprehensive feature-set. They are also extremely competent and professional engineers; I’ve hosted applications on Render for years and have very few complaints.

The Rewrite

The goal was to be able to run the database locally and test our migrations before applying them in production. We rewrote our data layer to treat the database as a simple persistence layer rather than an application. We eliminated all the triggers, stored procedures, and row-level security rules. That logic lives in the application now.

We dramatically simplified how we’re using the database and started using drizzle-orm to build SQL queries. It works like a dream. Now our database schema is captured in code, we can create pull requests with proposed database migrations, and nobody connects to the production database from their local computers. We were even able to eliminate a few tables because we could more efficiently query our data and define more accurate access controls.

The Migration

Migrating the data took a week. The first issue was how large our database is: 40gb.

We considered taking our service down for a couple hours to do the migration. But we’re a cloud service provider and we take that responsibility seriously: if we go down, that means our user’s API endpoints and cron jobs stop running. Downtime was our last resort.

The key insight was that 80% of our data was in our tracing table, which stores the historical evaluation of every Val Town function run. This was historical data and isn’t essential to operations, so we chose to first migrate our critical data and then gradually migrate this log-like table.

The next problem was improving the download and upload speeds. We spun up an ec2 sever next to Supabase in us-east-1 for the download and a server in Ohio Render region to be as close as possible for the downloads and upload,s respectively. After some more pg_dump optimizations, the download of everything but the tracing table took 15 minutes. We scp-ed it to the Render sever and did a pg_restore from there, which took another 10 minutes. We then cut our production servers over to the new Render Postgres database.

We informed our customers about the migration and that their tracing data would be restored shortly in the background. There was a handful of new data that had been created in the intervening ~30 minutes. We pulled that diff data manually, and uploaded it to the new database. The evaluations table dump took all night. Then the scp itself took a couple hours hours and $6 in AWS egress fees. It took another night to finish the upload of the historical tracing data.

Word to the wise: when you’re moving data into and out of databases, it pays to do it in the same network as the database servers.

Onwards and upwards

Now that Val Town is humming along with a simple Postgres setup on Render, we’re able to evolve our database with traditional, old-fashioned migrations, and develop the application locally. It feels strangely (back to the) future-istic to have migrations that run locally, in preview branches, and upon merging to main. I shipped likes (the ability to ❤️ a val) in a couple hours, and importantly, without anxiety. Back in our Supabase days, we delayed features like that merely because touching the database schema was scary.

Sometimes we miss the friendly table view of the Supabase interface. We watch their spectacular launch weeks with awe. Using Supabase was like peeking into an alternative, maybe futuristic, way to build applications. But now we’re spending our innovation tokens elsewhere, and have been able to ship faster because of it.

Edit this page